The curious case of disappearing bank branches

Will clicks take over bricks?

Scores of material on how bank branches will soon be a thing of the past is just a Google search away. In my quest to understand whether India is truly headed towards branchless banking, I skimmed through some numbers on the RBI website and others, and did some basic crunching, to make better sense of things as they stand.

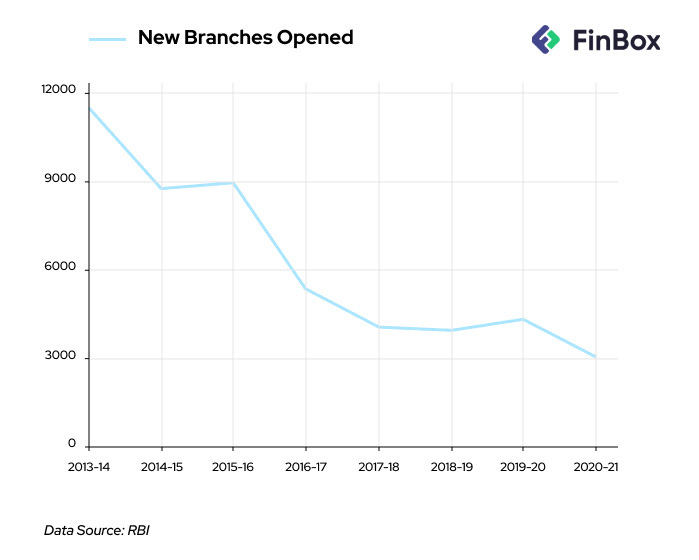

The rate at which banks (public, private, regional rural, and small finance banks) have been opening new branches has had a steep fall over the last eight years, with just a couple of upticks in an overall declining trend (see the chart below).

The upsurge observed in 2019 in the chart above has a significant contribution of public sector banks — 545 new branches were opened in 2019 (a 26% increase over the previous year). In the following year 641 new branches were opened by public sector banks (a ~17% increase over the previous year).

However, the picture becomes clearer only when one looks at data on branch closures. As many as 2118 branches of state-run banks closed or merged in the last fiscal. Hence, effectively, there has been a decline in the total number of operating branches. This proves that the shrinking trend of bank branches has been consistent in the last octennium.

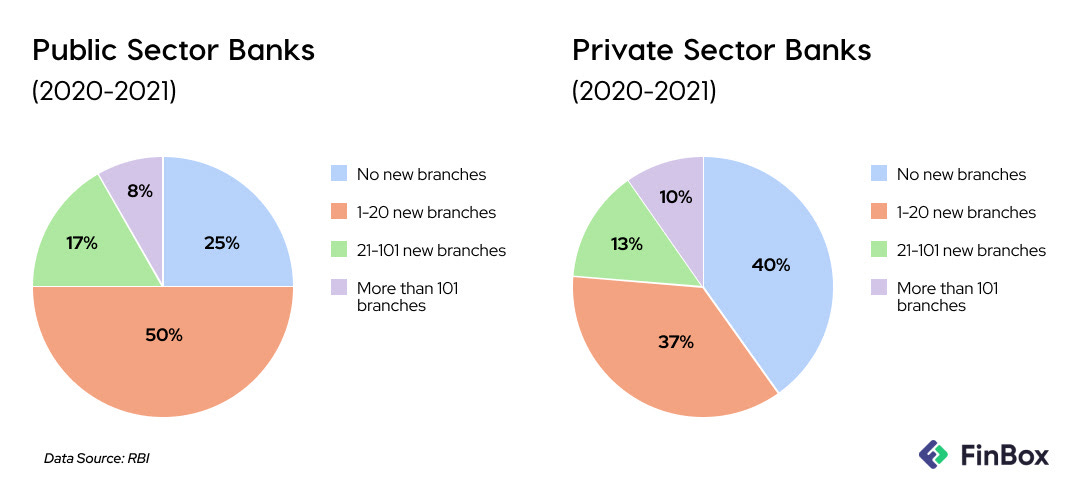

Another insight hiding in plain sight was the strikingly large number of blank cells in the time-series datasheet on new bank branches. In the fiscal year 2019-20, 58.3% of public sector banks and almost 38% of private banks opened less than five branches. In the next fiscal, 42% of public sector banks and 52% of private banks opened less than or equal to six branches a year (see the charts below).

In fact, a good number of these banks did not open any branches during the two fiscal years cited above (Please note: All the recently merged banks have been discounted in the above calculations so that the merger does not colour the insights from the above numbers).

Clearly, the share of new branches are those of relatively larger banks who can afford to expand, possibly unprofitably.

This leads us to certain pertinent questions. One, why are a large number of banks becoming highly reluctant to open new branches? Two, is it a lack of business viability that’s constricting expansion or are banks preoccupied with digital transformation?

Finding a definitive answer to the latter question may need deeper digging. However, there’s enough evidence that strongly suggests that Indian banks are very much in the digital game.

According to IBM’s IBV survey, India’s banking executives are becoming increasingly focused on employing big data and analytics tools. The survey also reveals that 67% of them are directing their organisations to improve the engagement and experience of their customers, compared to only 51% of global banking executives.

In addition, Indian banks are increasingly leveraging digital channels to offer services. For instance, in the case of SBI, only nine out of every 100 transactions happen in their branches. Besides, their transactions on ATMs, which used to comprise 55% of total transactions three years ago, have now declined to 30-32%.

Also, the banking industry’s convergence with businesses exploring new banking opportunities is increasing tremendously. All this points to extensive adoption of customer-first digital strategy. Hence, it would be more than conjecture to say that growing branchless-ness is a clear indicator of Indian banks’ shift to digital.

Branch out or root in?

Amidst this slump in the total number of branches, some major banks have recently floated the idea of improving rural inclusion through expansions of bank branches and business correspondents, all over again. If this was the solution to financial inclusion of rural India, it would have happened in over 60 years of branch-dominated banking. In truth, the absence of banking infrastructure in India’s villages is rather telling.

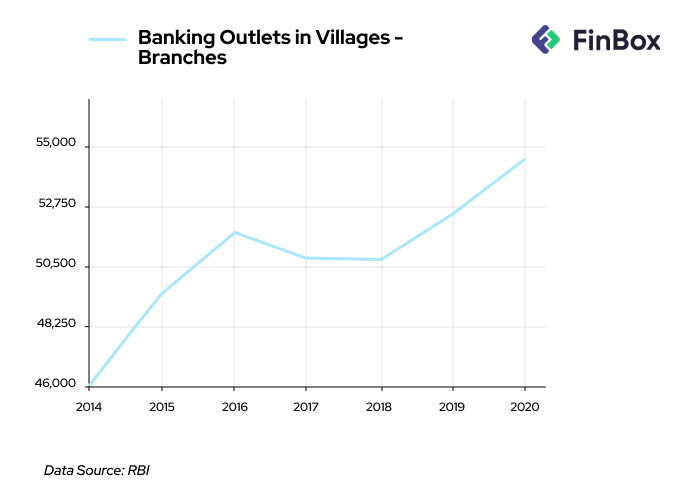

Branch-based banking has proven to be a high-cost, inefficient model, especially in rural India. In fact, between 2014 and 2016, at least 5,704 new branches were set up in villages. By 2018, over 1,025 of them were shuttered, data from the Reserve Bank shows. Thereafter, 1684 new branches have again been opened between 2018 and 2022 (see the chart below). Why open more branches only to shut them? Seems to me a rather vicious circle.

While Jan Dhan numbers tell a tall tale, data on account usage, financial literacy, savings and institutional borrowing say a different story. One out of 10 Jan Dhan accounts are inoperative. Trade volume growth of priority sector lending certificates came down from 43.1% in 2019 to 25.9% in 2020, indicating that credit flow to the sector cratered.

Also, savings in physical assets have consistently increased between 2015 and 2019. Above all, average financial literacy scores in India are low – at 11.9 out of 21 as calculated in data submitted by the finance ministry to the Rajya Sabha in January 2019. Evidently, India’s inclusion approach needs recalibration.

Let’s try and put this all into perspective. There is just one ATM for 10 villages in India. Access to banks is a major struggle. The interplay of social dynamics keeps the poor out of formal structures such as banks. On the other hand, internet adoption is skyrocketing in India’s hinterlands, with one out of four rural Indians having access to the internet.

The rural internet user base in 2020 was 299 million i.e, 21% of the rural population, according to The Internet and Mobile Association of India. And small towns account for almost two out of five active internet users. The internet enables individualized access and self-learning and can help overcome social barriers (caste and class barriers) to acquire financial literacy.

Would it be easier to encourage digital financial literacy or have them traverse miles to deal with patronizing staff and dilapidated ATM machines?

The era of digital villages is here. It’s time we jettison the idea of reverting to the old way of branches. While I have no desire to see bank branches disappear, I do not see how they can spearhead financial inclusion. To my mind, digital strategy should be the predominant theme of banking, supported and aided by flexible, asset-light branch models.